I would like to extend an invitation to everyone in this community to please browse, share, and fact check an interactive javascript timeline based on weather modification andgeoengineering.

As we all know there is not a definitive history of weather control, therefore I have put much effort into creating one. This page will grow over time, with many additions/corrections.

Each slide has an image, with reference links beneath the image.

Please send me any links to other timelines and reference material that can help me flesh this story out.

The History of Weather Control

http://www.terraforminginc.com/weather-control/

Thank you for your time.

Jim Lee

http://www.terraforminginc.com/

http://www.climateviewer.com/

Thursday, March 28, 2013

Sunday, March 17, 2013

Geoengineering Research Needs Better Guidelines, Climate Change Experts Say

Posted: 03/17/2013 2:14 pm EDT

FOLLOW:

With no clear rules to guide new research, scientists are shying away from examining whether geoengineering technologies can effectively cool the planet, and at what cost.

That’s the warning put forth by a pair of climate change experts in an essay published Thursday in the journal Science.

“This deadlock poses real threats to sound management of climate risk,” writeHarvard University climate scientist David Keith and UCLA environmental law expert Edward Parson. “Geoengineering may be needed to limit severe future risks, so informed policy judgments require research on its efficacy and risks."

Without that research, the world could face “unrefined, untested and excessively risky approaches” if climate change intensifies to the point that governments consider fighting it with geoengineering approaches, Parson and Keith said.

The researchers, who say the global debate over geoengineering is increasingly polarized, recommend that governments begin coordinating small-scale geoengineering research and block, at least for now, large-scale experiments.

They are not the first experts to recommend more geoengineering research. Over the past several years, the Bipartisan Policy Center, the U.K. Royal Society, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, the House Science, Space and Technology Committee, the American Geophysical Union and the Government Accountability Office have all called for more study to determine the efficacy and drawbacks of various proposed geoengineering techniques.

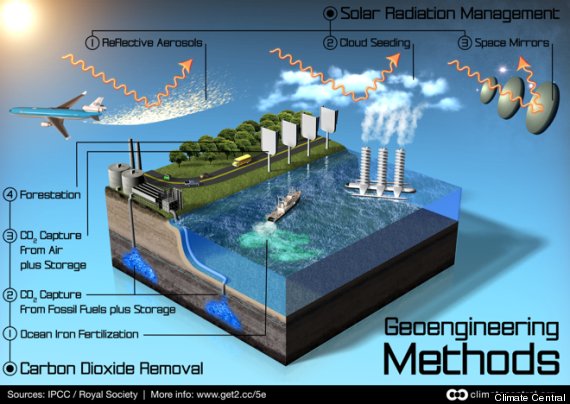

Parson and Keith zero in on one category of techniques to engineer a cooler planet — those that aim to reduce the amount of incoming sunlight that reaches Earth, which have drawn significant attention and controversy.

And unlike many earlier reports calling for geoengineering research, theirs attempts to define the size and scope of “large” and “small” experiments and lay out concrete steps governments and scientists should take to regulate the field.

“There is an increasing crystallization of opposing views and in the specific groups that have looked at this,” Parson said, “which kind of makes sense because of the natural tension that you feel when you look at these technologies: ‘Oh my goodness, we could really need something like this because we’re doing such a poor job at managing the primary problem, which is climate change. But oh my goodness, (geoengineering techniques) hold so many perils themselves.’”

But that has not stopped what Parson and Keith deem “rogue” experimentation, including an episode last year in British Columbia, Canada. An American businessman arranged to dump about 100 tons of iron sulfate into the Pacific Ocean in July in the hope of kickstarting a massive plankton bloom that would draw down carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

Researchers who study the ocean have warned that such experiments could have unknown, potentially harmful effects on marine ecosystems. Those concerns helped drive the U.N. Convention on Biodiversity and the London Convention, which regulates dumping of wastes into the ocean, to prohibit for-profit plans to fertilize plankton blooms with iron.

But despite those bans, when the American businessman Russ George undertook his experiment last summer near the islands of Haida Gwaii, the Canadian government was caught unaware.

And Parson and Keith argue the experiment, though ill-conceived, did not actually violate international law.

“The Haida case is a very good example of what you might fairly characterize as an experiment without controls, run without scientific organization,” Keith said. “We need the ability to regulate these things.”

He and Parson argue that governments should begin informal coordination to oversee small-scale field experiments that could help scientists understand how the atmosphere would respond to geoengineering — without having any significant effects on local climate conditions.

The category might include a small experiment to examine whether injecting sulfur compounds into the stratosphere destroys ozone molecules, or how spraying tiny particles of sea salt into the atmosphere affects cloud formation.

At the other end of the scale, Parson and Keith call for a government moratorium on experiments large enough to have a noticeable effect on regional or global climate conditions.

And there is little advantage to experiments that fall between those two extremes, they say.

“What I hope we are contributing is pointing out some quite effective things that cold be accomplished very simply and very quickly,” Keith said. “The experiments that could teach you a lot are very small, small compared to (the atmospheric effect of) things like trans-Atlantic airport flights.”

And a moratorium on large-scale experimentation could help allay the fears of people who worry that any research could make the actual use of geoengineering techniques a foregone conclusion.

Most importantly, both researchers said, studying geoengineering does not reduce the need for the world to cuts its greenhouse gas emissions, because geoengineering is not a long-term solution to climate change.

Their overall approach is sound, said Katharine Ricke, a postdoctoral fellow at the Carnegie Institution for Science who has published several studies evaluating different aspects of geoengineering. Her recent research suggests that economic incentives created by deploying geoengineering would drive governments to form small, exclusive coalitions, because the physical impact of geoengineering will vary widely around the globe.

"Every additional partner you bring in requires you to compromise on the setting of the global thermostat," Ricke said.

With that in mind, she said, "it's reasonable to assume that fostering international cooperation and inclusiveness and transparency in geoengineering research can probably only make it more likely that any implementation (of geoengineering) would be cooperative and inclusive and transparent."

Sunday, March 10, 2013

| ||

Saturday, March 9, 2013

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)